The Day The Ships Went Down

Part Two

Return to Part One

Off Outer Island

The Pretoria, meanwhile, was facing an equally perilous

situation. Struggling against the gale, the barge and her towing

steamer had managed to pass some 30 miles beyond the Apostles when

calamity struck: her steering gear failed. The Venezuela changed

course and began an effort to tow the disabled Pretoria back to

shelter in the lee of the islands. It was a desperate maneuver in the

wild seas, and it failed: the heavy towline snapped under the strain,

and the howling wind quickly swept the mammoth ship out of sight. The Venezuela turned back to search for her consort, but she was gone.

For several hours, the great ship drifted helplessly in the

waves.

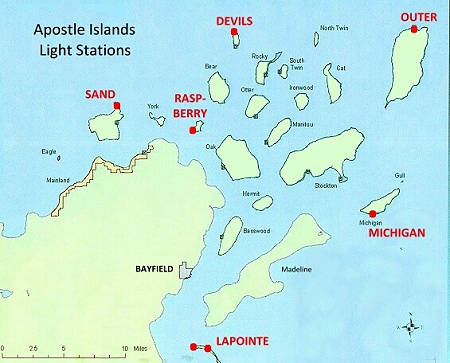

The great ships sank at opposite ends of the archipelago,

off Sand and Outer Islands.

Off Sand Island

The Sevona inched its way through the waves at slow speed.

Suddenly, though, there was a grinding jolt. Chief Engineer William

Phillippi recalled the moment:

"I received a signal from the captain to check the speed but

after she struck I received no more signals and I stopped the engine.

There were three distinct shocks and crashes, then the boat came to a

stand and broke in two. We blew the whistle for help until our fires

were put out."

Conditions aboard the grounded Sevona were desperate. The force

of the crash had split the boat in half. In the bow portion were the

captain and the officers; all of the experienced seamen. In the after

section were the engine-room crew, the passengers... and both of the

ship's lifeboats.

One of the passengers, Kate Spencer, described the scene:

"We got into the life boat at that time, but the captain and the

men could not come aft owing to the break. He hailed us through the

megaphone 'Hang on as long as you can.' We did so, but the sea was

pounding so hard, that we finally got out of the small boat, and into

the large vessel again, all congregating in the dining room which was

still intact.

"The big boat was pounding and tossing. Now a piece of the deck

would go, then a portion of the dining room, in which we were

quartered. During all this time, the men forward could not get to us.

Finally, at 11 o'clock everything seemed to be breaking at once, and

by order of the chief engineer, we took to the small boat again.

"One by one we piled into the boat, leaving six men behind us. I

never heard such a heart-rending cry as came from those six. 'For

God's sake don't leave us,' they cried.

Off Outer Island

What of the drifting Pretoria?

A newspaper account published two days later tells the tale:

"The Pretoria had a sail up forward, but the wind blew it to

ribbons. She was helpless in the trough of the sea. The waves

washed over her, and the wind was driving her in the direction of

Outer Island. The pumps were set at work but they gave out and the

anchor was dropped in 180 fathoms. It dragged some distance, but at

last brought up one and one half miles from the island and held.

"The seas pounded the distressed barge furiously. Water got into

the hold through the hatch combings.. the hatches came off and the

water poured into the hold. Then the covering board gave way and the

decks began to float off."

The crew of ten had only one hope: launch the lifeboat and head

through the storm to Outer Island.

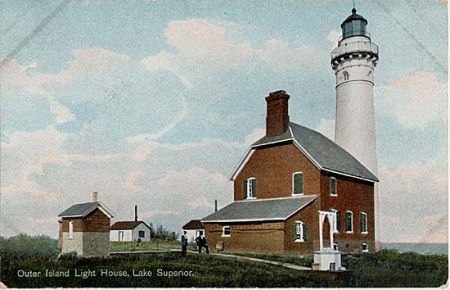

Postcard view of Outer Island Lighthouse

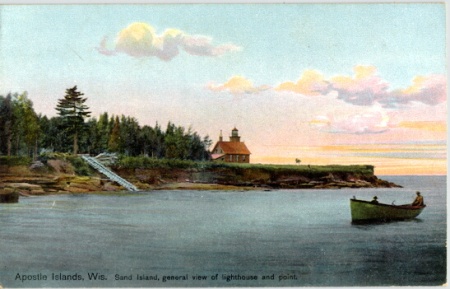

Off Sand Island

Stirred by the cries of their shipmates, several sailors set

their own safety aside and returned to help their comrades launch the

balky port lifeboat.

Now, two small boats pulled away from the dying Sevona; six in

one, eleven in the other. The port boat, with six aboard, headed

straight for Sand Island, where they made a successful landing and

quickly found shelter with fisherman Fred Hansen. Engineer

Phillippi, on the other boat, directed a valiant, but fruitless

attempt to rescue the men stranded on the forward section. Turning

finally toward the mainland, the lifeboat tossed in the waves for six

full hours before reaching shore at Little Sand Bay.

This was wild country in those days, but the castaways were lucky

to meet a farmer out looking for a lost cow. He led them to a

logger's cabin where they could rest and warm up. As soon as he

gathered strength, Phillippi set out by horse and wagon for Bayfield,

to seek aid for the seven men remaining on the wreck. It took him

nearly a full day to travel the eleven miles through the rough

country.

By the time he arrived, his comrades' fate was already sealed.

Working feverishly on the battered deck, Captain MacDonald and his

six companions improvised a raft from several hatch covers. When it

seemed the ship was about to break up, they launched the makeshift

craft and made for the island. It broke apart as they neared shore,

and all seven drowned in the surf.

Postcard view of Sand Island Lighthouse

On Outer Island

From his perch atop the Outer Island lighthouse, keeper John

Irvine could see the Pretoria's lifeboat pulling away. His dry words

in the lighthouse logbook recounts the scene:

"September 2- A terrible gale blowing from the NE, the biggest

sea that I have seen since I have been at the station, which is eight

years. About 2:30 PM, sighted a Schooner at anchor about two miles NE

of Station. About 4 PM seen small boat leaving Schooner."

Irvine was alone in the lighthouse that day; both his assistants

had gone to the mainland before the storm struck. At sixty-one years

of age, Irvine was not a young man. Born in the Orkney Islands of

Scotland, he'd come to the U.S. as a child and served with the Union

Army in the Civil War. He went to sea after the war, and spent years

as sailor himself before entering the Lighthouse Service.

Perhaps it was a sense of kinship with the desperate men in the

lifeboats that guided his next move. Grabbing a signal flag and a

rope, Irvine raced down the steep stairs from the lighthouse grounds

to the beach.

The sailors pulled at their oars, making slow progress against

wind and wave, painfully making their way to safety. Then, five

hundred feet from shore, the boat capsized, tossing the men every

which way. Five of the sailors were washed away to their doom; five

were able to hold on to the hull. As the overturned boat neared the

beach, Keeper Irvine did not hesitate. Wading out into the breakers,

he pulled the five men to shore, one by one.

Outer Island keeper John Irvine

with grandson, 1905

Continue to Part Three

|